Covidien Dialysis Catheter How Do You Know Which Lumen Is Atrial and Which Is Venous

- Example report

- Open Access

- Published:

Hemodialysis catheter insertion: is increased PO2 a sign of arterial cannulation? A case study

BMC Nephrology volume 15, Article number:127 (2014) Cite this article

Abstruse

Background

Ultrasound-guided Central Venous Catheterization (CVC) for temporary vascular admission, preferably using the correct internal jugular vein, is widely accepted by nephrologists. Nonetheless CVC is associated with numerous potential complications, including death. We describe the finding of a rare left-sided partial dissonant pulmonary vein connection during key venous catheterization for continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT).

Case presentation

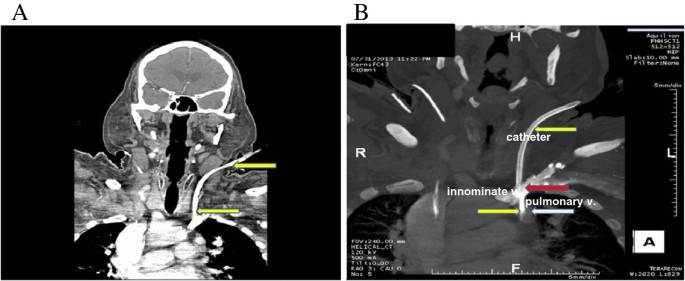

Ultrasound-guided cannulation of a big diameter temporary dual-lumen Quinton-Mahurkar catheter into the left internal jugular vein was performed for CRRT initiation in a 66 year old African-American with sepsis-related oliguric acute kidney injury. The post-procedure chest X-ray suggested inadvertent left carotid avenue cannulation. Blood gases obtained from the catheter showed high fractional pressure of oxygen (PO2) of 140 mmHg and low partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2) of 22 mmHg, suggestive of arterial cannulation. However, the pressure-transduced moving ridge forms appeared venous and Computed Tomography Angiography located the catheter in the left internal jugular vein, only demonstrated that the tip of the catheter was lying over a left pulmonary vein which was abnormally draining into the left brachiocephalic (innominate) vein rather than into the left atrium.

Conclusion

Although several mechanical complications of dialysis catheters take been described, ours is 1 of the few cases of malposition into an anomalous pulmonary vein, and highlights a sequential approach to properly identify the catheter location in this uncommon clinical scenario.

Background

Central venous catheterization (CVC) using a big bore catheter (>7 French) is widely used in renal patients for hemodynamic monitoring, rapid infusion of fluids and blood products, antibiotic administration, parenteral nutrition, and vascular access for hemodialysis and continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT). Ultrasound (US)-guided CVC for temporary vascular access, preferably using the right internal jugular vein (IJV), is widely accepted past nephrologists [i]. Compared to the subclavian approach, right IJV is the preferred site because of easier catheterization, high rate of success when using only anatomical landmarks of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and straighter path to the superior vena cava [2]. Withal CVC is associated with numerous potential complications, including expiry. Near mechanical complications occur early, during the puncture of the target vessel or catheter advocacy, with subsequent development of hemorrhage, pseudoaneurysms, arteriovenous fistula, arterial dissection, neurological injury and severe or lethal airway obstruction [3, 4]. Therefore, nephrologists and nephrology trainees should not but be trained in temporary vascular access placement, but also exist informed about techniques to place or differentiate successful venous punctures from arterial punctures, equally well as how to prevent and manage process-related complications [1, two].

Case presentation

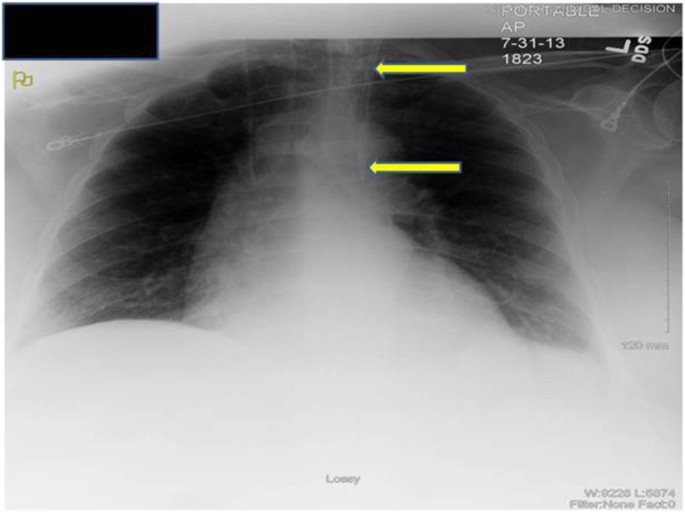

A 66 year old man with underlying chronic kidney illness, presumed secondary to hypertension, presented to the emergency room with one-week history of weakness, fatigue and poor oral intake. The patient was hypotensive (systolic blood force per unit area of 60 mmHg) and had severe azotemia (serum creatinine of 4.9 mg/dl class baseline of one.7 mg/dl). Septic shock, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and oliguric acute kidney injury were diagnosed. The patient was adequately resuscitated with intravenous fluids, vasopressors and broad-spectrum antibiotics, later narrowed to cefazolin. The source of infection was unclear after broad investigation of body fluids and imaging studies. Despite an initial transient clinical improvement, the patient remained in shock with high vasopressor requirements, became anuric and developed acute mental status changes. As a consequence, the conclusion to start the patient on CRRT was made. Nosotros inserted a 13.5 French diameter temporary dual-lumen Quinton-Mahurkar catheter (Covidien, Inc.) into the left IJV under United states guidance. Although the right IJ is preferred, the intensive intendance unit of measurement team had already inserted a triple-lumen cardinal venous catheter in this site for hemodynamic monitoring and fluid and medication assistants. The initial puncture with an 18-guess needle into the left IJV using real-fourth dimension US guidance was successful with non-pulsatile dorsum-catamenia and venous (dark red) claret appearance. After, after removal of the ultrasound transducer, the rest of the procedure was performed without any resistance to advancing the guidewire and catheter by the Seldinger technique [5]. Good menstruation of dark cherry blood was obtained from both catheter lumens. However, the routine post-cannulation chest X-ray (Figure one) showed that the tip of the catheter was not crossing the midline to the right side and the tip appeared to be lying over the aortic curvation suggesting inadvertent carotid artery cannulation. We then obtained blood gas assay from the catheter which showed: pH of vii.34, partial pressure of oxygen (POii) of 140 mmHg and partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2) of 22 mmHg, likewise suggestive of arterial cannulation. The vascular surgery team was emergently consulted. A pressure level transducer was attached to the catheter and showed venous moving ridge forms. To definitively determine the location of the catheter, a Computed Tomography Angiography (CTA) of the head and neck was obtained. The CTA showed the Quinton-Mahurkar catheter extending into the left IJV and later on descending to terminate in an dissonant left upper lobe pulmonary vein, only inferior to its anomalous insertion in the left brachiocephalic (innominate) vein (Figures 2A and B). Interestingly, manipulation of the catheter under fluoroscopy past interventional radiology showed that the left brachiocephalic (innominate) vein failed to cross the midline to empty into the right atrium, confirming the venous anomaly. The catheter was therefore removed and a new similar catheter was placed in the right IJV. CRRT was then initiated and continued uneventfully until the patient's critical condition improved.

Chest Radiography. Chest-X ray showing the Quinton-Mahurkar catheter tip (yellow arrow) non crossing the midline to the right side.

Computed Tomography Angiography (CTA). (A) CTA showing Quinton-Mahurkar catheter (yellowish arrow) extending into the left IJV and after descending to end in an anomalous left upper lobe pulmonary vein, only inferior to its dissonant insertion in the left brachiocephalic vein; (B) CTA showing Quinton-Mahurkar catheter (yellow arrow), left brachiocephalic (innominate) vein (red pointer) and anomalous pulmonary vein (white arrow) draining into the left brachiocephalic (innominate) vein.

Conclusion

Over v million catheters are placed annually in the United States, most of the fourth dimension for hemodialysis procedures [6]. In comparison to traditional bullheaded CVC insertion techniques using superficial anatomical landmarks, CVC nether US guidance achieves higher success rates, including fewer needle attempts, rapid vein localization and fewer complications [7, 8]. However, inadvertent arterial trauma or cannulation under US guidance notwithstanding occurs. Amidst the various mechanical complications of CVC, unintended arterial puncture has been reported to occur in up to viii% of cases [ane]. Because this complication is oft recognized by getting pulsatile, vivid crimson blood earlier the catheter is introduced into the claret vessel, inadvertent arterial catheterization is much less common, <0.one% [two, 4]. In almost cases of misplacement, the catheter follows an unpredicted pathway into the vena cava tributaries, a complication observed in xl cases of a series of two,580 patients. In three of these patients, the abnormal location resulted from a persistent left superior vena cava [ix]. The risk factors associated with CVC complications include obesity, short cervix and urgent catheterization [4].In patients with hypotension, depression hemoglobin and hypoxemia, the visual signs of pulsatile, bright red blood suggestive of arterial puncture might be missed [2, 4, x].

When visual discrimination between arterial and venous blood is unreliable, confirmation should be pursued using all available resources (Tabular array 1). One of these is to attach a pressure level transducer to the catheter and discriminate between venous and arterial waveforms [ten]. This method is non always effective, particularly in patients with severe hypotension, atrial fibrillation, constrictive pericarditis or severe pulmonary hypertension with tricuspid regurgitation [2]. Another method is the use of blood gas assay, in which high PO2 is suggestive of arterial blood. This could be misleading in certain situations. For example, high blood POtwo from a central venous catheter was reported in a patient who had the catheter properly placed in the IJV but a shunt in his right arm from his arteriovenous fistula was supplying arterial blood to the superior vena cava via the axillary and subclavian veins [11]. Similarly to our patient, at that place is a case of unexpected high blood PO2 from the dialysis catheter in a patient with anomalous pulmonary vasculature [12]. Although pressure transduction testing and blood gas analysis yield useful information and are easy to perform and obtain, they are not 100% reliable and have to be interpreted in the proper clinical context. Since the complications of arterial cannulation are pregnant (eastward.g., massive stroke, hemorrhagic shock) and its delayed recognition could be devastating, confirmatory imaging studies are necessary. About malpositioned central venous catheters can be identified with frontal and lateral chest radiographs [13]. If doubtfulness about the location of the catheter persists later on chest radiography, a CTA –if intravenous iodinated contrast is not contraindicated– should be obtained to ostend malposition [14, 15].

If arterial trauma with a large caliber catheter occurs, prompt surgical or endovascular intervention is probable the safest approach. The pull and pressure technique (removal of the catheter followed past external compression) is associated with significant chance of hematoma, airway obstruction, stroke and pseudoaneurysm, specially when the site of the arterial trauma cannot exist finer compressed. Endovascular treatment appears to exist safety for the direction of arterial injuries that are difficult to expose surgically, such equally those below or behind the clavicle [16].

Our patient had a partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection (PAPVC). PAPVC is a congenital anomaly present in 0.4 to 0.7% of postmortem examinations. Nigh xc% of all PAPVCs originate from the correct lung, vii% from the left lung and iii% from both lungs. The common drainage sites are the superior vena cava, the inferior vena cava, right atrium and brachiocephalic (innominate) vein [12, 17, 18]. Most of these anomalies are discovered incidentally during routine radiographic evaluation of the lungs washed for other reasons. In isolated PAPVC, the patient is usually asymptomatic if anomalous venous render is less than l% of total pulmonary venous blood. Some patients could develop cardio-respiratory symptoms if there is pregnant left-to-right shunt, which is associated with other cardiac anomalies (10 to 15% of those with atrial septal defects have PAPVC). The majority of patients with a left PAPVC, as in the case of our patient, accept a skillful long term prognosis [12].

In summary, the placement of a dialysis catheter in a vein draining pulmonary venous blood due to anomalous pulmonary venous connection may pb to apparent arterial cannulation (loftier PO2 in blood gas analysis). Our case highlights the available methods to properly identify the catheter location in a patient with a rare congenital pulmonary vascular malformation and the importance of prompt Computed Tomography Angiography for definitive diagnosis before surgical or invasive interventions.

Consent

The patient was deceased at the time of preparation of this manuscript. Written informed consent was obtained from his adjacent-of-kin for publication of this Case Study and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

References

-

Choi JI, Cho SG, Yi JH, Han SW, Kim HJ: Unintended cannulation of the subclavian artery in a 65-year-old-female for temporary hemodialysis vascular access: management and prevention. J Korean Med Sci. 2012, 27 (10): 1265-1268. 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.ten.1265.

-

Choi YS, Park JY, Kwak YL, Lee JW: Inadvertent arterial insertion of a key venous catheter: delayed recognition with abrupt changes in pressure waveform during surgery -A example report. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2011, sixty (one): 47-51. ten.4097/kjae.2011.60.one.47.

-

Schummer W, Schummer C, Rose N, Niesen WD, Sakka SG: Mechanical complications and malpositions of central venous cannulations past experienced operators. A prospective study of 1794 catheterizations in critically sick patients. Intensive Intendance Med. 2007, 33 (vi): 1055-1059. 10.1007/s00134-007-0560-z.

-

Pikwer A, Acosta S, Kolbel T, Malina M, Sonesson B, Akeson J: Management of inadvertent arterial catheterisation associated with primal venous access procedures. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009, 38 (half dozen): 707-714. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2009.08.009.

-

Seldinger SI: Catheter replacement of the needle in percutaneous arteriography; a new technique. Acta Radiol. 1953, 39 (5): 368-376. x.3109/00016925309136722.

-

Wadhwa R, Toms J, Nanda A, Abreo Chiliad, Cuellar H: Angioplasty and stenting of a jugular-carotid fistula resulting from the inadvertent placement of a hemodialysis catheter: instance report and review of literature. Semin Dial. 2012, 25 (4): 460-463. 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2011.01005.ten.

-

Gilbert TB, Seneff MG, Becker RB: Facilitation of internal jugular venous cannulation using an audio-guided Doppler ultrasound vascular access device: results from a prospective, dual-eye, randomized, crossover clinical study. Crit Care Med. 1995, 23 (1): lx-65.

-

Milling TJ, Rose J, Briggs WM, Birkhahn R, Gaeta TJ, Bove JJ, Melniker LA: Randomized, controlled clinical trial of bespeak-of-care limited ultrasonography assistance of central venous cannulation: the Third Sonography Outcomes Assessment Plan (Lather-3) Trial. Crit Care Med. 2005, 33 (eight): 1764-1769.

-

Sobrinho G, Salcher J: Partial anomalous pulmonary vein drainage of the left lower lobe: incidental diagnostic later on key venous cannulation. Crit Intendance Med. 2003, 31 (iv): 1271-1272.

-

Jobes DR, Schwartz AJ, Greenhow DE, Stephenson LW, Ellison Due north: Safer jugular vein cannulation: recognition of arterial puncture and preferential use of the external jugular route. Anesthesiology. 1983, 59 (iv): 353-355. x.1097/00000542-198310000-00017.

-

Aghdami A, Ellis R: Loftier oxygen saturation does non e'er bespeak arterial placement of catheter during internal jugular venous cannulation. Anesthesiology. 1985, 62 (3): 372-373. 10.1097/00000542-198503000-00036.

-

Chintu MR, Chinnappa S, Bhandari South: Aberrant positioning of a primal venous dialysis catheter to reveal a left-sided fractional anomalous pulmonary venous connection. Vasc Health Run a risk Manag. 2008, 4 (5): 1141-1143.

-

Boardman P, Hughes JP: Radiological evaluation and management of malfunctioning key venous catheters. Clin Radiol. 1998, 53 (i): 10-sixteen. 10.1016/S0009-9260(98)80027-five.

-

Patel RY, Friedman A, Shams JN, Silberzweig JE: Central venous catheter tip malposition. J Med Imag Radiat Oncol. 2010, 54 (1): 35-42. 10.1111/j.1754-9485.2010.02143.x.

-

Gibson F, Bodenham A: Misplaced fundamental venous catheters: practical anatomy and practical management. Br J Anaesth. 2013, 110 (3): 333-346. 10.1093/bja/aes497.

-

Guilbert MC, Elkouri S, Bracco D, Corriveau MM, Beaudoin Due north, Dubois MJ, Bruneau 50, Blair JF: Arterial trauma during primal venous catheter insertion: Case series, review and proposed algorithm. J Vasc Surg. 2008, 48 (4): 918-925. 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.04.046. give-and-take 925

-

Sasikumar N, Ramanan S, Chidambaram S, Rema KM, Cherian KM: Bilateral anomalous pulmonary venous connection to bilateral superior caval veins. Globe J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2014, 5 (1): 124-127. 10.1177/2150135113498784.

-

ElBardissi AW, Dearani JA, Suri RM, Danielson GK: Left-sided partial anomalous pulmonary venous connections. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008, 85 (3): 1007-1014. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.11.038.

Pre-publication history

-

The pre-publication history for this paper tin be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2369/15/127/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to Monique Clark for expert graphic assistance. ARR is supported by the NIDDK (DK091316) and the American Order of Nephrology Gottschalk Honour.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Boosted information

Competing interests

Dr. Rodan has received a speaker's fee from Eli Lilly that was not related to this case written report. The remaining authors declare that they take no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

Analysis of patient'due south clinical course and outcomes: JCC, Jan, JP, and ARR; drafting of the manuscript: JCC and JAN; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: JCC, January, and ARR. Administrative, technical, and material support: JCC and JAN. All authors read and canonical the concluding manuscript.

Authors' original submitted files for images

Rights and permissions

This commodity is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Artistic Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/iv.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in whatsoever medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the information made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Nigh this article

Cite this commodity

Chirinos, J.C., Neyra, J.A., Patel, J. et al. Hemodialysis catheter insertion: is increased PO2 a sign of arterial cannulation? A example report. BMC Nephrol 15, 127 (2014). https://doi.org/x.1186/1471-2369-15-127

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1186/1471-2369-15-127

Keywords

- Hemodialysis

- Catheter

- Cardinal venous cannulation

- Vein anomaly

Source: https://bmcnephrol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2369-15-127

0 Response to "Covidien Dialysis Catheter How Do You Know Which Lumen Is Atrial and Which Is Venous"

Post a Comment